With the divisive discord that permeates the news and our conversations, I think about the dearth of liberals in our world. There are plenty of liberals, you might say. No, there are plenty of progressives. There’s a difference.

The term “liberal” has been perverted to refer to political progressives, when it actually means being broad-minded and tolerant of people with different views. You can be conservative and be liberal. Consider Columnist David Brooks.

Few people are able to maintain a strong ideology and be open to opposing points of view.

A friend of mine, Al Sondej, was a wonderful example of being liberal. Al was singularly focused on battling world hunger, while being open and friendly to those who didn’t understand why he did what he did.

Al’s focus was unmistakable. The first time I saw him was the spring of 1975. He was standing in front of a dining hall at the University of Notre Dame with a cutout milk jug, collecting money for hunger relief overseas, chanting, “A penny buys three bowls of porridge, a dime buys 30.”

He was there the next day and next day and, finally, every day, even in the middle of a rain storm, always with a smile, talking about the imbalanced distribution of world resources. He collected daily, during both the lunch and the dinner hours, for about two years.

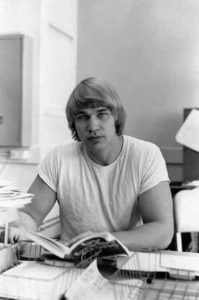

Al hardly had the look of someone who was dedicated to fighting hunger. He was big as a house, built like a freight train and reputed at one time to be the strongest man on campus. The photo you see doesn’t do him justice. Supposedly, at one time he was one of the campus’ most prolific beer drinkers.

Al’s life changed abruptly one day. After a close friend committed suicide, Al rethought his priorities. He stopped drinking, stopped lifting weights, moderated his consumption of food (so as not to consume more than his fair share of the world’s resources), decided he would never own a car (same reasoning that caused him to eat less), took courses on the global economy, wrote articles on the subject and collected donations. He made the issue of world hunger his life’s work and became a one-man army fighting hunger.

But the cause didn’t consume Al. It just made him influential in a subtle way.

Al’s daily collections violated Notre Dame’s “no solicitation” policy. Al was committed to collecting money, and the university didn’t want to make exceptions. University president, Fr. Ted Hesburgh, just looked the other way.

After talking with Al, my father felt compelled to conduct a special Thanksgiving collection in 1976 in Steubenville, Ohio. He collected money at the center of the town, holding a cut-out milk jug, just as Al did, and persuaded city schools and restaurants to take part in his campaign. Altogether he raised close to $6000 in just a few weeks.

After talking with Al, my father felt compelled to conduct a special Thanksgiving collection in 1976 in Steubenville, Ohio. He collected money at the center of the town, holding a cut-out milk jug, just as Al did, and persuaded city schools and restaurants to take part in his campaign. Altogether he raised close to $6000 in just a few weeks.

Though Al was uncompromising about hunger relief, he always retained a sense of humor and enjoyed life. Whether people disagreed with him about his work didn’t matter.

Al was tolerant of everyone.

He never tried forcing his ideology on anyone, but if you wanted to learn more about the global poverty, Al was there to teach.

After Notre Dame, Al pursued graduate studies at the University of Maryland. As he did at Notre Dame, he supported himself by serving in a fire department. He died in 1988 while searching for someone he believed to be trapped inside a burning house.

Few people can live such focused lives and still be open-minded. It seems we’re trained to be intolerant.

Maybe the difference comes with humility, and Al was plenty humble. He never judged others or insisted he was right. He simply pursued his life’s work for the purpose of doing well.

As simple as it sounds, modeling Al is a tall order, but wouldn’t life be much more comfortable if we all did.

_____________________________________

Jack D’Aurora writes for considerthisbyjd.com

___________________________________________________

Also published on Medium.

I first ran across someone calling themself a “progressive” back in 2003 or so. They asked me if I was one. I said “I don’t know, what is a ‘progressive?” They shrugged and said something like…”someone that thinks progressively”. Since then I ask the same question and get variations of the same answer. I’ve decided that for many (haven’t spoken to all of them) that as the term “liberal” carries such negative connotations (self imposed in my opinion) they keep looking for new labels to assign. Having been discarded by my own party for not following the party line I can appreciate what many have gone through in the recent elections. So rather than try to find a label for myself, I’m starting to think that maybe it would be better for me to wait and see if a label can come find me. Al seems like a great guy. I think I’ll remember him without a label.

What a great friend to have! Notice present tense! Hopefully you realize he he still has a presence thru you!